Topics A-Z

Acidification (Ocean)

The ocean absorbs around 30% of the annual emissions of anthropogenic CO2 to the atmosphere, helping to alleviate the impacts of climate change on the planet. The ecological costs to the ocean, however, are high, as the absorbed CO2 reacts with seawater and changes the acidity of the ocean, affecting life in the ocean as well as ocean services such as transport, fisheries and tourism. Observations from open ocean sources over the last 20 to 30 years have shown a clear trend of decreasing average pH, caused by increased concentrations of CO2 in seawater. In order to characterize the variability of ocean acidification, and to identify the drivers and impacts, a high temporal and spatial resolution of observations is crucial. The Sustainable Development Goal Target 14.3 specifically addresses ocean acidification and the associated Indicator calls for the measurement of marine acidity (pH).

Our work on Ocean Acidification

IOC is the custodian agency for the SDG Target 14.3 (ocean acidification) and its Indicator calling for "average marine acidity (pH) measured at agreed suite of representative sampling stations". As such, IOC is responsible for the development of the corresponding methodology, the collection of data towards the SDG Indicator from Member States and the submission of annual reports to the UN.

IOC is part the Global Ocean Acidification Observing Network (GOA-ON) whose goals include expanding ocean acidification observations, closing human and technology capacity gaps, connecting scientists regionally and globally, and informing about the impacts of ocean acidification.

IOC and the Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR) sponsor the International Ocean Carbon Coordination Project (IOCCP), an ocean carbon monitoring and research programme.

IOC participates in the Ocean Acidification international Reference User Group (OA-iRUG) and is on the Advisory Board of the Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre (OA-ICC) of the IAEA.

The IOC Sub-commission for the Western Pacific (WESTPAC) has organized training for scientists in the Western Pacific region so that experts and oceanographic institutions from the region and beyond can work together to improve monitoring of ocean acidification and to track changes in coral reef ecosystems. WESTPAC’s training efforts have focused on standardizing the approaches needed to monitor the ecological impacts of ocean acidification on coral reef ecosystems across all countries in the region.

Biodiversity

Probably one million or more marine species call Ocean home. The ocean covers not only 71% of Earth's surface, it is also more than 99% of our biosphere (Earth’s habitable space). Life originated in the ocean and still holds the highest variety of unique forms of life of any ecosystem on this planet. The importance of species diversity for marine ecosystem functioning is well known. However, our knowledge of ocean biodiversity is highly variable and very deficient. Less than 10% of the ocean had any long-term biological sampling in the last 10 years, and the sampling that did occur was focused close to developed areas of the globe. To monitor and assess biodiversity and to support science-based decisions it is important that we gain a much better understanding of where species live, why, in what abundance, and how these factors are changing through time.

Our Work on Biodiversity

The Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS) is one of our flagship data systems. OBIS is a global data platform that integrates, quality controls and provides access to over 60 million occurrence records of 135,000 different marine species and that number is growing by millions every year. OBIS is built by the contribution of thousands of scientists who collaborate with data managers to make scientific data available for research, management and public awareness. Every year, OBIS is used in over 100 scientific papers. The UN World Ocean Assessment and the assessments as part of the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services all use OBIS to report on the state of our ocean.

In collaboration with the GOOS Biology and Ecosystems Panel, the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and UNEP's World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), we are developing standard data flows and publication for all components of the Marine Habitat Properties through OBIS. All components of these Essential Ocean Variables are being considered as headline indicators for the CBD Post-2020 global biodiversity framework.

One of the major threats to ocean biodiversity are invasive species transported by human activity. The Pacific islands Marine bioinvasions Alert Network (PacMAN) project of the IOC aims to develop a monitoring program for marine invasive species in the Pacific SIDS (small island developing states). In collaboration with local stakeholders in Fiji and the University of the South Pacific, as well as scientific experts from the marine field, PacMAN will utilize environmental DNA methods to provide early warnings of invasive species. We will develop a decision support tool for policy makers, and in this way facilitate the protection of the marine ecosystem and the services it provides.

For the IOC Intergovernmental Panel on Harmful Algal Blooms we are maintaining and developing a global data and information system on harmful microalgae and the harm they cause via the OBIS data platform and connecting with complementary databases.

Blue Carbon

The term “blue carbon” refers to the carbon stored in coastal and marine ecosystems. The so-called blue carbon ecosystems – mangroves, tidal and salt marshes, and seagrasses – are highly productive coastal ecosystems that are particularly important for their capacity to store carbon within the plants and in the sediments below. Scientific assessments show that they can sequester two to four times more carbon than terrestrial forests and are thereby considered a key component of nature-based solutions to climate change.

Healthy blue carbon ecosystems also provide habitat for marine species, support fish stocks and food security, sustain coastal communities and livelihoods, filter water flowing into our oceans and reef systems, and protect coastlines from erosion and storm surges. They are found on every continent except Antarctica and cover approximately 49 million hectares.

Despite their importance, coastal blue carbon ecosystems are some of the most threatened ecosystems on Earth. They are being degraded or destroyed at four times the rate of tropical forests and climate change threatens to accelerate these losses. Nearly 50% of the pre-industrial, natural extent of global coastal wetlands have been lost since the 19th century. This decline continues today, with estimated losses of ∼0.5–3% annually depending on ecosystem type. Mangrove forest exploitation, urban and industrial coastal development, pollution, and pressures from agriculture and aquaculture are some of the common causes for coastal ecosystem degradation. Due to their high carbon content, blue carbon ecosystems can turn into significant sources of greenhouse gas emissions when degraded or lost. The ongoing carbon losses from blue carbon ecosystems are estimated to account for up to 19% of emissions from global deforestation.

Our work on Blue Carbon

IOC is engaged at the scientific and policy levels with the vision to protect, manage or restore global blue carbon ecosystems (mangroves, seagrasses and tidal/salt marshes) for addressing climate change.

The Blue Carbon Initiative (BCI) – co-organized by IOC, Conservation International (CI) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – works to develop management approaches, financial incentives and policy mechanisms for ensuring the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of coastal blue carbon ecosystems. It engages local, national, and international governments in order to promote policies that support coastal blue carbon conservation, management and financing. The goal is to develop comprehensive methods for assessing blue carbon stocks and emissions, which will be implemented by projects around the world that demonstrate the feasibility of blue carbon accounting, management and incentive agreements.

Since 2015, the IOC is Partner of the International Partnership for Blue Carbon (IPBC) and since 2020 is sharing the Coordinator role with the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. The aim of the Partnership is to provide an open forum for government agencies, non-governmental organisations, intergovernmental organisations and research institutions to connect, share and collaborate to build solutions, take actions, and benefit from the experience and expertise of the global community, with a vision to protect, sustainably manage and restore global coastal blue carbon ecosystems. The Partnership was launched at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris in 2015 by nine founding Partners and has since expanded to more than 54 Partners in 2022.

Blue Economy

The Blue Economy concept seeks to promote economic growth, social inclusion, and the preservation or improvement of livelihoods while at the same time ensuring environmental sustainability of the oceans and coastal areas.

At its core, it refers to the decoupling of socioeconomic development through oceans-related sectors and activities from environmental and ecosystems degradation. An important challenge of the Blue Economy is thus to realize that the sustainable management of ocean resources requires collaboration across nation-states and across the public-private sectors, at global scale (World Bank, 2017).

Our work on Blue Economy

Linked to its work on Marine Spatial Planning (MSP), the IOC promotes an approach to the Blue Economy based on the integration of economic, environmental and social concerns.

By promoting the establishment of MSP plans and creating an environment conducive to transnational cooperation through the development of international guidance for cross-border and transboundary MSP, the MSPglobal Initiative aims at improving planning of sustainable economic activities at sea.

The SPINCAM Project establishes an integrated coastal area management indicator framework at national and regional level in the countries of the Southeast Pacific region, addressing the state of the coastal and marine environment and socio-economic conditions. Indicators related to the Sustainable Blue Economy, with their corresponding methodology, data and sub-indicators, have been developed for the region.

Capacity Development

The majority of IOC Member States are developing countries or countries in economic transition. The IOC Capacity Development Programme aims at assisting Member States in acquiring the necessary (human) capacity to equitably participate in IOC activities and to enable them to sustainably develop and manage their coastal areas.

IOC has established 3 regional sub-commissions that have a strong and self-driven Capacity Development focus. IOC also adopted its Capacity Development Strategy 2015-2021. The strategy has 6 expected outputs. IOC aims at assisting Member States with implementing these. In addition IOC is embarking on the development of the Ocean InfoHub which will allow discovery of and access to a wide variety of information and data, contributing to Capacity Development.

Climate

The world ocean is an integral part of the climate system: the coupling processes and feedback mechanisms among atmosphere, ocean, land surface, and cryosphere will determine the features and behavior of the climate system of the future.

Since the industrial revolution, the ocean has evolved into a major sink for carbon generated by human activities. Without oceanic and terrestrial sinks, atmospheric CO2 levels would be close to 600 ppm (parts per million), well above the level compatible with a global warming target limited to 2 ̊C.

In the context of climate change, however, it is still unclear to scientists if the ocean will continue to help mitigate the effects of global warming, or its capacity to absorb carbon from the atmosphere will be altered as a consequence of the numerous human-induced ocean changes.

The world ocean absorbs roughly 28% of the excess CO2 emissions thus acting as the equal second reservoir of anthropogenic CO2 together with terrestrial ecosystems. This comes with a price: the ocean has become significantly more acidic, which can affect the ability of marine organisms such as plankton, mollusks, and reef-building corals to build and maintain shells and skeletal material. The ocean has also warmed significantly in modern times, which has an impact on marine organisms and also on the distribution of oxygen and the emergence of "dead" (extremely poor in oxygen) zones. This more acidic, warmer, and poor in oxygen world ocean has clear effects in terms of reduced ecosystem functioning for ecosystem services such as climate mitigation and food security.

Our work on Climate

The Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO is at the forefront of climate science and knowledge that inform and underpin meaningful actions to counteract climate change:

- The World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) – an endeavor of IOC, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the International Science Council (ISC) – acts as an authoritative international platform to craft and implement the next generation of the research agenda on climate and climate change. WCRP is also responsible for developing the models on which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) bases its scenarios and, therefore, negotiations and decisions on climate change are based.

- IOC conducts work on the effects of CO2 emissions on ocean acidification and acts as a custodian agency for SDG Target Indicator 14.3.1 on ocean acidity.

- Faced with the urgent need to find answers to this and other crucial scientific questions, five international research programmes on ocean and climate interaction (IOCCP, IMBeR, SOLAS, WCRP/CLIVAR and the Global Carbon Project) have joined IOC to develop and agree on a roadmap for future research, with the ultimate goal of providing decision-makers with the knowledge needed to implement effective climate change mitigation and adaptation policies in the next ten years.

- IOC, WMO, the International Science Council (ISC) and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) co-sponsor the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), which provides an increasingly comprehensive platform to integrated in situ and remote observations of the status of the world ocean and climate and climate change.

- The IOC portfolio of activities on early warning systems of tsunami events and other ocean hazards entails inter alia systematic observations of sea level and changes therein, which is of direct relevance to vulnerability and risks of coastal communities and ecosystems related to the effects of climate change.

- IOC coordinates the International Partnership for Blue Carbon and co-hosts the Blue Carbon Initiative, contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation, biodiversity and livelihoods.

- Additionally, the IOC activities aimed at supporting climate adaptation in member states include a well-proven and increasingly widely applied methodology for marine spatial planning, including in relation to multi-stakeholder dialogues based on science that are aimed at developing agreed climate change adaptation plans.

Data and Information

The programme International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE) of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO was established in 1961. Its purpose is to enhance marine research, exploitation and development, by facilitating the exchange of oceanographic data and information between participating Member States, and by meeting the needs of users for data and information products.

The IODE programme coordinates a global network of more than 100 National Oceanographic Data Centres (NODCs), Associate Data Units (ADUs) and Associate Information Units (AIUs). These centres manage and make available millions of ocean observations that contribute to ocean data products and services developed and used by other IOC programmes. The IODE programme includes more than 15 specific projects.

Deep Sea

Novo denique perniciosoque exemplo idem Gallus ausus est inire flagitium grave, quod Romae cum ultimo dedecore temptasse aliquando dicitur Gallienus, et adhibitis paucis clam ferro succinctis vesperi per tabernas palabatur et conpita quaeritando Graeco sermone, cuius erat inpendio gnarus, quid de Caesare quisque sentiret. et haec confidenter agebat in urbe ubi pernoctantium luminum claritudo dierum solet imitari fulgorem. postremo agnitus saepe iamque, si prodisset, conspicuum se fore contemplans, non nisi luce palam egrediens ad agenda quae putabat seria cernebatur. et haec quidem medullitus multis gementibus agebantur.

Deoxygenation (Ocean)

Oxygen is critical to the health of the planet. It affects the cycles of carbon, nitrogen and other key elements, and is a fundamental requirement for marine life from the seashore to the greatest depths of the ocean. Nevertheless, deoxygenation, the reduction of oxygen, is worsening in the coastal and open ocean. This is mainly the result of human activities that are increasing global temperatures (CO2-induced warming) and increasing loads of nutrients from agriculture, sewage, and industrial waste, including pollution from power generation from fossil fuels and biomass.

15 things to know about the declining oxygen in the world’s ocean:

- Oxygen is critical to the health of the ocean. It structures aquatic ecosystems and is a fundamental requirement for marine life from the intertidal zone to the greatest depths of the ocean.

- Oxygen is declining in the ocean. Since the 1960s, the area of low oxygen water in the open ocean has increased by 4.5 million km2, and over 500 low oxygen sites have been identified in estuaries and other coastal water bodies.

- Human activities are a major cause of oxygen decline in both the open ocean and coastal waters. Burning of fossil fuels and discharges from agriculture and human waste, which result in climate change and increased nitrogen and phosphorus inputs, are the primary causes.

- Deoxygenation (a decline in oxygen) occurs when oxygen in water is used up at a faster rate than it is replenished. Both warming and nutrients increase microbial consumption of oxygen. Warming also reduces the supply of oxygen to the open ocean and coastal waters by increasing stratification and decreasing the solubility of oxygen in water.

- Dense aquaculture can contribute to deoxygenation by increasing oxygen used for respiration by both the farmed animals and by microbes that decompose their excess food and faeces.

- Insufficient oxygen reduces growth, increases disease, alters behaviour and increases mortality of marine animals, including finfish and shellfish. The quality and quantity of habitat for economically and ecologically important species is reduced as oxygen declines.

- Finfish and crustacean aquaculture can be particularly susceptible to deoxygenation because animals are constrained in nets or other structures and cannot escape to highly-oxygenated water masses.

- Deoxygenation affects marine biogeochemical cycles; in particular phosphorus availability, hydrogen sulphide production and micronutrients.

- Deoxygenation may also contribute to climate change through its effects on the nitrogen cycle. When oxygen is insufficient for aerobic respiration, microbes conduct denitrification to obtain energy, a process that produces N2O – a powerful greenhouse gas.

- The problem of deoxygenation is predicted to increase in the coming years. Continued greenhouse gas emissions are expected to enhance global warming and in consequence deoxygenation. The global discharge of nitrogen and phosphorus to coastal waters may increase in many regions of the world as human populations and economies grow. It is expected that many areas will experience more severe and prolonged hypoxia than at present.

- Slowing and reversing deoxygenation will require reducing greenhouse gas emissions globally and decreasing nutrient discharges that reach coastal waters. Concerted international efforts can reduce carbon emissions.

- The decline in oxygen in the ocean is not happening in isolation. At the same time, food webs are disturbed due to overfishing and physical destruction of habitats, and waters are getting warmer, more acidic, and experiencing higher nutrient loads. Management of marine resources will be most effective if the cumulative effects of human activities on marine ecosystems are considered.

- More accurate predictions of ocean deoxygenation, as well as improved understanding of its causes, consequences and solutions, require expanding ocean oxygen observation, long-term and multi-stressor experimental studies, numerical modelling and historical and paleo reconstructions.

- Publicly available, accurate oxygen measurements with appropriate temporal resolution and spatial coverage in the marine environment are needed to document the current status of our ocean, to track changing conditions, to build and validate models that can project future oxygen levels, and to develop strategies to slow and reverse deoxygenation.

- Steps required to slow or reverse ocean deoxygenation can directly benefit marine biodiversity and human health and well-being. Sewage treatment and limiting global warming, for example, will improve marine ecosystem health with societal benefits that extend beyond improving oxygen in our ocean and coastal waters.

Our work on Deoxygenation

The Global Ocean Oxygen Network (GO2NE) – IOC working group is committed to providing a global and multidisciplinary view of deoxygenation, with a focus on understanding its multiple aspects and impacts.

The Network’s research, outreach, and capacity building efforts include facilitating communication with other established ocean science and observation networks and programmes in working groups (e.g. IOCCP, GOOS, GOA-ON, GlobalHAB, WESTPAC O2NE, IMBeR, Future Earth Ocean KAN, SOLAS). The Network’s aim is to improve observation systems, identify and fill knowledge gaps, as well as develop and implement capacity building activities worldwide. GO2NE’s communication efforts include the website ocean-oxygen.org, supported by GO2NE, which provides the latest information on deoxygenation to scientists, stakeholders and the interested public and a monthly webinar, which offers the possibility to listen to two scientists (one junior and one senior) presenting the underlying mechanisms and impacts of ocean deoxygenation.

Global Ocean Oxygen Decade (GOOD): GO2NE and partners are part of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. From 2021 to 2030, the Ocean Decade programme GOOD – Global Ocean Oxygen Decade - will raise global awareness about ocean deoxygenation, provide knowledge for understanding causes, attributing changes and developing actions for mitigation and adaptation measures through local, regional and global efforts, including intensified monitoring, transdisciplinary research, bi-directional knowledge transfer among stakeholders and scientists, innovative outreach and ocean education and literacy. The high-level objective of the Decade Programme is to provide data, knowledge, highly qualified personnel via capacity building and best practices to enable society, stakeholders, and scientists to co-design and develop measures that can mitigate the drivers and impacts of ocean deoxygenation and provide appropriate adaptation measures where mitigation is not possible. Developing mitigation of and/or adaptation approaches to deoxygenation are of paramount importance for ensuring the provision of ecosystem services, addressing threats to the climate system and minimizing the impact of ocean deoxygenation on the ocean economy.

Outreach documents

Kiel Declaration on Ocean Deoxygenation

Ocean deoxygenation: Everyone’s problem (IUCN, 2019)

Ocean Deoxygenation: A Hidden Threat to Biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (DOSI, 2019)

Ocean oxygen in the Ocean Observing System Report card 2021

Science Documents

Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters (Science, 2018)

System controls of coastal and open ocean oxygen depletion (Progress in Oceanography, 2021)

Early Career Professionals (Oceanscience)

The Ocean Decade Early Career Ocean Professional (ECOP) programme is an initiative launched by the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) with the aim of empowering and engaging young professionals to drive ocean science and innovation.

The Ocean Decade ECOP programme provides a platform for early-career ocean professionals from around the world to connect, collaborate, and exchange knowledge and ideas. It seeks to support the development of the next generation of ocean leaders, while fostering a diverse and inclusive community of ocean professionals.

The programme includes a range of activities and opportunities for ECOPs, including mentorship and training programmes, networking events, and research and innovation challenges. These activities are designed to help ECOPs develop the skills, knowledge, and networks they need to drive ocean science and innovation, and to contribute to the goals of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

The Ocean Decade ECOP programme is an important component of the broader effort to promote sustainable ocean development and advance our understanding of the ocean's role in global sustainability. By supporting the development of the next generation of ocean professionals, the programme aims to ensure that we have the talent and expertise needed to address the complex and pressing challenges facing our ocean and our planet.

Early Warning

Ocean hazards, such as storm surges, tsunamis or biohazards, can be devastating for the coasts and their communities. They can also have lasting and damaging effects on the coastal landscape, causing long-term coastal erosion, and on marine ecosystems.

Our work on Early Warning

IOC assists and advises policy makers and managers in the reduction of risks from harmful algal blooms, tsunamis, and other coastal hazards by focusing on implementing adaptation measures to strengthen the resilience of vulnerable coastal communities, their infrastructure and service-providing ecosystems.

When it comes to ocean biohazards, they fall into several categories, of which the most important is the production of toxins by some species of algae. When these organisms proliferate, they become known as harmful algal blooms (HABs) which can have profound effects on coastal ecosystems seafood safety, and human health.

The IOC Harmful Algal Blooms Programme is designed to foster the effective management of, and scientific research on, harmful algal blooms in order to understand their causes, predict their occurrences, and mitigate their effects. Concepts and national capacity for early warning systems on HAB are developed in close collaboration with FAO (Food Agricultural Organization) and IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency).

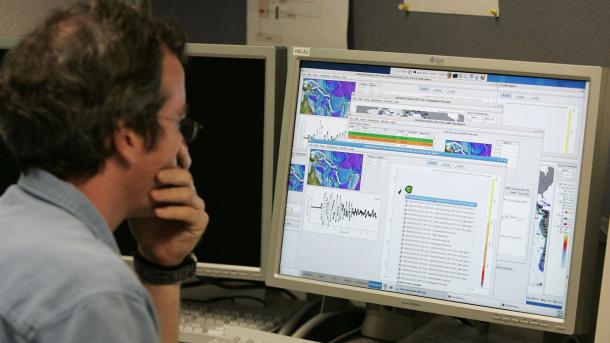

With regards to tsunamis, the IOC Tsunami Programme aims at reducing the loss of lives and livelihoods that could be produced worldwide by tsunamis. The IOC Tsunami Unit supports IOC Member States in assessing tsunami risk, implementing Tsunami Early Warning Systems (EWS) and in educating communities at risk about preparedness measures. After forty years of experience coordinating the Pacific Tsunami Warning System (PTWS), IOC-UNESCO is now leading a global effort to establish ocean-based tsunami warning as part of an overall multi-hazard disaster reduction strategy in order to provide adequate protection a the local, regional, national and global scale.

Eutrophication / Nutrients

Nutrient over-enrichment of coastal ecosystems is a major environmental problem globally, contributing to problems such as harmful algal blooms, dead zone formation, and fishery decline. Yet, quantitative relationships between nutrient loading and ecosystem effects are not well defined.

Our work on Eutrophication / Nutrients

The IOC Nutrients and Coastal Impacts Research Programme (N-CIRP) is focussing on integrated coastal research and coastal eutrophication, and linking nutrient sources to coastal ecosystem effects and management in particular. As part of the implementation strategy for N-CIRP, IOC also actively participates in a UNEP led Global Partnership on Nutrient Management (GPNM) with intergovernmental organizations, non-governmental organizations and governments.

Concern over the impacts of altered nutrient inputs, N, P and Si, to coastal waters has led the UN to include an “Index for Coastal Eutrophication Potential” (ICEP) as indicator for SDG Goal 14.1.1 on eutrophication. To implement ICEP it is needed to develop a dissolved silica model and evaluate the effectiveness of ICEP in predicting coastal impacts at the global scale. With UN Environment being the custodian agency for 14.1.1, the IOC is aiming at contributing by developing and validating ICEP fully.

Gender

Women that have dedicated their lives to marine sciences and to the protection of the marine environment have agreed to share their stories, and to help us understand how IOC-UNESCO can work together with them in the promotion of gender equality. Their testimonials will hopefully encourage women and girls to pursue careers in ocean science.

Francesca Benzoni

Marine biologist specialized in the ecology and integrated systematics of reef building scleractinian corals (France)

Anela Choy

Assistant Professor of Oceanography, Scripps Institution of Oceanography (USA)

Lisa Levin

Director, Center for Marine Biodiversity & Conservation, Scripps Institution of Oceanography | Distinguished Professor, Scripps Institution of Oceanography (USA)

Ruby Moothien Pillay

Principal Research Scientist, Mauritius Oceanography Institute

Savithri (Savi) Narayanan

Dominion Hydrographer | Director General Ocean Science, Canadian Hydrographic Service, Department of Fisheries and Oceans

Nadia Pinardi

Associate Professor of Oceanography and Meteorology, University of Bologna | Director, Italian National Group of Operational Oceanography, Instituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia

Yunne-Jai Shin

Senior Researcher, Institut de recherche pour le développement (France) and University of Cape Town (South Africa)

Liana Talaue-McManus

Scientist of Marine Affairs, Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science, University of Miami (USA)

Harmful Algal Blooms

Phytoplankton blooms, micro-algal blooms, toxic algae, red tides, or harmful algae, are all terms for naturally occurring phenomena. About 300 hundred species of micro algae are reported at times to form mass occurrence, so called blooms. Nearly one fourth of these species are known to produce toxins. The scientific community refers to these events with a generic term, "Harmful Algal Bloom" (HAB), recognizing that, because a wide range of organisms is involved and some species have toxic effects at low cell densities, not all HABs are "algal" and not all occur as "bloom".

Proliferations of microalgae in marine or brackish waters can cause massive fish kills, contaminate seafood with toxins, and alter ecosystems in ways that humans perceive as harmful. A broad classification of HABs distinguishes two groups of organisms: the toxin producers, which can contaminate seafood or kill fish, and the high-biomass producers, which can cause anoxia and indiscriminate kills of marine life after reaching dense concentrations.

Our Work on Harmful Algal Blooms

The overall goal of the HAB Programme embraces a range of scientific and managerial challenges: to foster the effective management of, and scientific research on, harmful algal blooms in order to understand their causes, predict their occurrences, and mitigate their effects.

Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM)

The IOC launched its institutional strategy to support its Member States in developing Integrated Coastal Area Management (ICAM) in 1997. Since then, countries have adapted the priority objectives of the ICAM Strategy to current needs to support the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 14 (“Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”) of the 2030 Agenda.

Coastal and marine ecosystem-based management and planning to ensure sustainability

The IOC builds collective capacities to respond to emerging ocean issues through ecosystem and area-based management tools such as Integrated Coastal Area Management, Marine Spatial Planning and Sustainable Blue Growth initiatives, including transboundary and large-marine ecosystem approaches for the sustainable use of marine resources, with a view to achieve a healthy and a productive ocean.

Coastal and marine hazards adaptation and preparedness through ecosystem-based and area-based management tools to keep coastal communities safe

Together with its Member States and partners, the IOC promotes the integration of ocean-related hazards and climate change adaptation within coastal and marine management and planning tools in order to improve preparedness and resilience of coastal communities.

Coastal and marine data, information and decision support tools to know more about our ocean

The IOC continues supporting the increase of collective knowledge and management actions on the status and change of coastal and marine ecosystems and sustained services through use and dissemination of data, information and decision support tools.

Useful links:

Large Marine Ecosystems

Large marine ecosystems (LMEs) are regions of the world's oceans, encompassing coastal areas from river basins and estuaries to the seaward boundaries of continental shelves and the outer margins of the major ocean current systems. They are relatively large regions on the order of 200,000 km² or greater, characterized by distinct bathymetry, hydrography, productivity, and trophically dependent populations. Productivity in LME protected areas is generally higher than in the open ocean.

Although the LMEs cover mostly the continental margins and not the deep oceans and oceanic islands, the 66 LMEs produce about 80% of global annual marine fishery biomass. In addition, LMEs contribute USD 12.6 trillion in goods and services each year to the global economy. Due to their close proximity to developed coastlines, LMEs are in danger of ocean pollution, overexploitation, and coastal habitat alteration.

Our work on Large Marine Ecosystems

Since 1997, IOC has promoted the Large Marine Ecosystem approach from a scientific point of view as well as in regions by contributing to the formulation and implementation of Global Environment Facility (GEF) LME projects. The Global Environment Facility has provided support (USD 285 million, leveraging USD 1.14 billion in financing from other partners) to 124 recipient countries to work together within 23 of the world’s 66 LMEs.

The GEF LME:LEARN (Large Marine Ecosystems Learning Exchange and Resource Network) is a project financed by GEF, implemented by UNDP and executed by IOC-UNESCO, aiming to improve global ecosystem-based governance of LMEs and their coasts by generating knowledge, building capacity, harnessing public and private partners and supporting south-to-south learning and north-to-south learning. The hitherto implementation of the project has contributed, inter alia, to the High Level Objective 1: Healthy Ocean Ecosystems and Sustained Ecosystem Services, of the IOC Medium-Term Strategy for 2014–2021, by building local and regional capacities, in terms of knowledge and tools, for implementing ecosystem based approaches in the marine environment.

Law of the Sea

With its unique mandate in ocean science and services, the IOC is a recognized competent International Organization in the fields of Marine Scientific Research (Part XIII) and Transfer of Marine Technology (Part XIV) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (10 December 1982), also referred to as “the Constitution of the Oceans”.

IOC is responsible for documenting the practice of Member States in Marine Scientific Research as well as for the implementation of the IOC Criteria and Guidelines on the Transfer of Marine Technology (CGTMT) adopted in 2005 by the IOC Assembly. These criteria and guidelines aim at applying the provisions of Part XIV (Development and transfer of marine technology) UNCLOS, providing a critical tool to promote capacity building in ocean and coastal related matters through international cooperation. Through the CGTMT, the IOC hopes to inspire national actions, legislation, projects, and programmes, as the concept of Transfer of Marine Technology represents a true opportunity in international cooperation under the IOC umbrella.

IOC is also charged with updating the list of experts for special arbitration in the field of MSR and TMT (Annex VIII of UNCLOS) and providing support to the “Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf” and Member States in relation to the submissions for the extension of the continental shelf.

Marine Pollution

Novo denique perniciosoque exemplo idem Gallus ausus est inire flagitium grave, quod Romae cum ultimo dedecore temptasse aliquando dicitur Gallienus, et adhibitis paucis clam ferro succinctis vesperi per tabernas palabatur et conpita quaeritando Graeco sermone, cuius erat inpendio gnarus, quid de Caesare quisque sentiret. et haec confidenter agebat in urbe ubi pernoctantium luminum claritudo dierum solet imitari fulgorem. postremo agnitus saepe iamque, si prodisset, conspicuum se fore contemplans, non nisi luce palam egrediens ad agenda quae putabat seria cernebatur. et haec quidem medullitus multis gementibus agebantur.

Marine Spatial Planning

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) is a public process of analysing and allocating the spatial and temporal distribution of human activities in marine areas to achieve ecological, economic and social objectives that have been specified through a political process.

MSP is not an end in itself but a practical way to create and establish a more rational use of marine space and the interactions among its uses, to balance demands for development with the need to protect the environment, and to deliver social and economic outcomes in an open and planned way.

Our work on Marine Spatial Planning

Since organizing the first International Workshop on MSP in 2006, the IOC has become a leading institution promoting science-based, integrated, adaptive, strategic and participatory concepts worldwide. Its first guide “Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach toward Ecosystem-based Management” (2009) became an internationally recognized standard that contributed to formulating the conceptual approach behind MSP.

In March 2017, following the second International Conference on MSP, the IOC adopted the “Joint Roadmap to accelerate MSP processes worldwide” (MSProadmap) with the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (DG MARE), aiming to triple maritime areas under national jurisdictions benefiting from MSP by 2030. To support the first years of the roadmap implementation, the MSPglobal Initiative (2018 - 2021) – co-financed by the European Union – was designed with the main objective of developing the new “MSPglobal International Guide on Marine/Maritime Spatial Planning”, which was published in 2021. With the support of national, regional and international partners, the IOC has provided technical assistance to several activities under the MSProadmap.

The IOC work on MSP also extends to other related initiatives, which it leads as the executing agency. Within the Global Environment Facility (GEF) funded, UNDP/UNEP implemented GEF IW:LEARN Phase 5 (2022 - 2026), for example, IOC steers the capacity building activities related to MSP in collaboration with an extensive partner network. By bringing in the experience and results generated by MSPglobal in support of MSP as a tool for strengthening blue economy opportunities, the IOC plays a vital role in integrating MSP into the science to policy process of Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) projects funded by GEF.

In 2021, the IOC joined the new coalition Ocean Action 2030, dedicated to providing countries of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) with assistance to develop and implement Sustainable Ocean Plans. A Sustainable Ocean Plan is an ‘umbrella’ framework for ocean-related governance that aims to guide decision-makers and stakeholders on how to sustainably manage maritime areas under national jurisdiction. As an area-based plan, MSP is considered a key component of a Sustainable Ocean Plan.

Within UNESCO, the IOC has also fostered collaboration with the Man and Biosphere Programme and the World Heritage Marine Programme, demonstrating the value of MSP tools in developing marine conservation plans.

Useful links:

MSProadmap and MSPglobal Initiative

Observations (Ocean)

Long term ocean observations allow us to better understand climate change and variability, and improve our forecasting of climate, weather, ocean status and environmental hazards and their impacts. Ocean information supports good policy and provides an evidence base for real-time decision-making, tracking the effectiveness of management actions, and guiding adaptive responses on the pathway to sustainable development. Developing our ability to provide relevant information at global, regional, and down to coastal scales, is vital to addressing local needs and building resilience. In addition to supporting sustainability, ocean knowledge and information have the power to generate profits and jobs in the marine economy. By 2030, the ocean economy, buoyed by growth in tourism, mariculture and renewable energy, is predicted to be a much larger component of our national economies.

Our work on Ocean Observations

The Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS) plays an essential role in coordinating the world’s distributed ocean observing systems. Together, with a broad ocean observing community, GOOS provides a pathway for the evolution of an integrated global system, ensuring that it meets the needs of the diverse array of end-users.

In the past three decades, GOOS and the global science community have made good progress on the development and coordination of ocean observations. Today, these observations provide the backbone for ocean and weather forecasts, deliver understanding of the ocean’s role in the global climate system, as well as the climate's impact on the ocean.

To meet the growing demands of policy makers, private sector users and the general public, we need a step change in the breadth and extent of the ocean observing system. We need a fully integrated global observing system that captures essential physical, chemical, biological, and ecological ocean properties, from global to local coastal scales - the Global Ocean Observing System 2030 Strategy is the pathway to achieve this.

Established in 1991, GOOS is co-sponsored by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO, the World Meteorological Organization, the United Nations Environment Programme, and the International Science Council.

Useful links:

Ocean Decade

The vision of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) is the "science we need for the ocean we want". The Ocean Decade is a convening framework for diverse stakeholders to co-design and co-deliver solution-oriented research needed for a well-functioning ocean in support of the 2030 Agenda. Capacity development, ocean literacy and the removal of barriers to full gender, generational, and geographic diversity are essential elements of the Decade.

Since 2018, over 2,000 stakeholders have been consulted to develop the Ocean Decade Implementation Plan that provides a non-prescriptive framework for Decade implementation. Two peer review processes generated nearly 300 submissions on the draft Plan from IOC Member States, UN agencies, and other stakeholders. An Executive Planning Group including representatives of Early Career Ocean Professionals provided advice on the Plan’s development.

The Plan documents the Decade outcomes that describe the "ocean we want" by 2030. It describes a series of ten Ocean Decade Challenges that will unite partners around common ocean science priorities related to knowledge gaps, essential infrastructure, capacity development, and behavior change. These Actions - taking the form of programs, projects, activities or contributions - will be implemented throughout the Decade to create collectively the Ocean We Want and help achieve the 2030 Agenda and related global policy frameworks.

Regular Call for Decade Actions are planned throughout the entirety of the Ocean Decade.

The Decade will promote the emergence of an extensive stakeholder engagement network including National Decade Committees, regional and thematic stakeholder fora. All of these networks assemble around the Ocean Decade's Global Stakeholder Forum to co-design and co-deliver the innovative science we need to improve our understanding and management of a more sustainable ocean.

Ocean Literacy

Most of us live our lives blissfully unaware of how our day-to-day actions impact on the health of the ocean, or how the health of the ocean impacts on our own daily lives. Ocean literacy is defined as "an understanding of the ocean’s influence on you and your influence on the ocean". An ocean literate person is able to understand the importance of the ocean for humankind, is able to communicate about the ocean in a meaningfully way, and has a more responsible and informed behaviour towards the ocean and its resources.

Our work on Ocean Literacy

The ocean literacy framework and approach has been developed by a group of educators and scientists in the United States, and then taken up, and adapted by European, Asian and African scientists and educators. While all these organizations and associations have been critical to promote ocean literacy nationally and regionally, the need for an international collaboration and exchange of good practices and experiences led to the engagement of the IOC-UNESCO in ocean literacy. The IOC promotes the dissemination and the use of ocean literacy materials and resources to schools and students from all around the world, manages an ocean literacy portal which acts as one-stop-shop for ocean literacy resources, and organizes training and capacity development activities in collaboration with other IOC units and with the Ocean Teacher Global Academy. The IOC furthermore collaborates with media, philantropies, artists, scientists and educators to develop innovative tools and approaches to fully leverage ocean knowledge to promote ocean sustainability

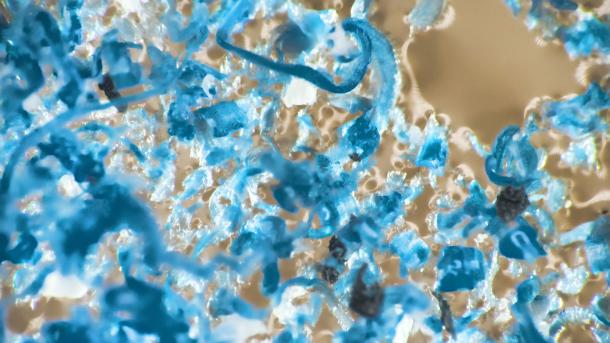

Plastics (Marine)

It is widely recognised that marine litter can have significant ecological, social and economic impacts. Plastics form a large proportion of marine litter, and the widespread occurrence of macroscopic plastic debris and the direct impact this can have both on marine fauna and legitimate uses of the environment, sometimes remote from industrial or urban sources, has been well documented. Plastic debris comes in a wide variety of sizes and compositions and has been found throughout the world ocean, carried by ocean currents and biological vectors (e.g. stomach contents of fish, mammals and birds). Plastics degrade extremely slowly in the open ocean, partly due to UV absorption by seawater and relatively low temperatures. In recent years the existence of micro-plastics and their potential impact has received increasing attention. The extent of the impact of plastic litter in the oceans is uncertain, despite the considerable scientific effort that has been expended in recent years.

Our work on Marine Plastics

The IOC is actively engaged in and sponsoring a UN multi agency working group on "Sources, Fate and Effects of plastics and micro-plastics in the marine environment". This is within the Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection (GESAMP) which is an advisory body, established in 1969, that advises the United Nations (UN) system on the scientific aspects of marine environmental protection.

Science (Ocean)

There is no commonly accepted definition of ocean science.

Ocean science includes all research disciplines related to the study of the ocean: physical, biological, chemical, geological, hydrographic, health, and social sciences, as well as engineering, the humanities, and multidisciplinary research on the relationship between humans and the ocean. Ocean science seeks to understand complex, multi-scale social-ecological systems and services, which requires observations and multidisciplinary and collaborative research.*

*Definition presented by the Expert Panel on Canadian Ocean Science in the report “Ocean Science in Canada: Meeting the challenge, seizing the opportunity (Council of Canadian Academies, 2013)

Our work on Ocean Science

The IOC ocean science portfolio of activities are prioritized around four strategic themes or clusters: science in support of sustainability of ocean ecosystems in a changing environment; assessing and predicting ocean health and variations in ocean goods and services; responding to governments; and science for the unknown sea.

IOC activities on ocean science address: blue carbon, harmful algal blooms, acidification, deoxygenation, climate change, eutrophication/nutrients, marine engineering, plastics (marine), time series, modelling and predictions and multiple ocean stressors.

Additionally, IOC contributes to building capacities in ocean science. In this regard, the Global Ocean Science Report 2017: The Current Status of Ocean Science around the World assessed for the first time the status and trends in ocean science capacity around the world. The report offers a global record of who, how, and where ocean science is conducted: generating knowledge, helping to protect the ocean health and empowering society to support sustainable ocean management in the framework of the United Nations 2030 Agenda.

The Global Ocean Science Report 2020: Charting Capacity for Ocean Sustainability (GOSR2020) addresses four additional topics: contribution of ocean science to sustainable development; blue patent applications; extended gender analysis; and capacity development in ocean science.

The GOSR2020 is a resource for policymakers, academics and other stakeholders seeking to assess progress towards the sustainable development goals of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, in particular SDG target 14.a on scientific knowledge, research capacity and transfer of marine technology. The GOSR provides the information for the indicator for target 14.a as the proportion of total research budget allocated to research in the field of ocean science. GOSR2020 not only provides consistent reference information at the start of United Nations Decade for Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030), it evolves as a living product. The global community is given the online facility to submit and update data on the GOSR portal and consult data to regularly assess progress on the efficiency and impact of policies to develop ocean science capacity.

Useful links:

Global Ocean Science Report 2020: Charting Capacity for Ocean Sustainability

Global Ocean Science Report 2017: The Current Status of Ocean Science around the World

Science Policy

The IOC strives to increase knowledge about the ocean and coastal areas, and to apply that knowledge for the improvement of management, sustainable development, protection of the marine environment, and the decision-making processes of its 150 Member States.

The IOC participates in numerous ocean related global partnerships and forums to bridge the science-policy interface. It provides relevant and timely technical advice to governments and policy-makers to make informed decisions on scientific issues related to ocean management at the national and global levels and to develop policy to support the development of a sustainable ocean economy. In order to bring the scientific and policy-making communities closer together and encourage mutual understanding, IOC promotes ongoing dialogue, access to a wide range of scientific assessments and targeted capacity development initiatives to strengthen the science-policy interface at all levels.

IOC is a participant or observer in key global discussions related to the ocean including the High Level Political Form for the 2030 Agenda, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) processes. IOC routinely provides technical and scientific support to a number of global assessments relevant to the ocean, such as the UN World Ocean Assessment, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), as well as assessment initiative of other UN agencies such as the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), CBD and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). It supports Member States engaging in these processes for example by developing policy briefs providing scientific and technical analyses for use by negotiators, and decision-makers.

Seabed Mapping

The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) is working to map the floor of the global ocean. The oceans cover over two-thirds of our planet but it's often said that we know more about the shape of the surface of Mars than we do about the bottom of our own ocean.

The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) operates under the joint auspices of the IOC and the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). It involves a group of international experts in seafloor mapping who are working together to develop a range of bathymetric data sets and data products for scientists and resource managers.

Sustainable Development Goals (SDG)

The IOC holds a universal mandate and global convening power for ocean science and capacity development in support of the 2030 Agenda and its sustainable goals. With a strong regional presence in Africa, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific, the IOC provides field expertise in all ocean basins, and works in cooperation with UN and international partners to coordinate ocean-related activities in 148 Member States.

Over its 55 years, UNESCO’s IOC has developed a strong outreach capacity to mobilize national policy makers, scientific institutions and civil society toward conserving ocean health; coordinating early warning systems for ocean hazards such as tsunami; ensuring ecosystem resilience to climate change; and constantly developing knowledge of emerging ocean issues.

UNESCO and its IOC have shared UN leadership in core areas of the 2030 Agenda. The IOC contributed in formulating the Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14), which calls on Member States to conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources. The IOC is actively supporting the preparations for a major UN Conference to Support the Implementation of SDG 14 (New York, 5-9 June 2017).

The IOC is moreover engaged in other United Nations ocean-related processes, such as the World Ocean Assessment, the negotiations on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity in the high seas, and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. These processes may go beyond the 2030 Agenda, but they are essential to the achievement of the sustainable development goals.

UNESCO’s IOC provides important contributions to the implementation of the 2030 Agenda’s global goals in a number of areas:

Capacity development and transfer of marine technology

Agenda 2030 explicitly highlights the IOC’s role through the transfer of marine technology in developing Member States’ capacities to protect the ocean and sustainably use its ecosystem services. IOC resources and convening power help to develop capacities of Member States as well as to broker innovation and learning in national scientific communities. The IOC will engage in the development of a UN wide technology transfer facilitation mechanism to support SDG implementation by Member States.

Demonstrated monitoring, assessment and benchmarking capacities

The IOC has wide expertise for analysing the state of the ocean, building on operational programmes such as the Global Ocean Observing System. The IOC is also responsible for monitoring a set of SDG 14 “ocean” indicators, based on regional and global internationally comparable data from the Transboundary Waters Assessment Programme (TWAP), the IOC Global Ocean Science Report (GOSR), and a global network of national ocean data centers.

Cross cutting mandate relevant to other SDGs

The IOC is involved in monitoring the role of the ocean in the climate system and improving disaster risk reduction, providing a major contribution to implementing SDG 13 on climate change and SDG 11 on sustainable cities. Considering the significant impact of the ocean on several aspects of our daily lives, IOC activities also strengthen efforts to achieve other global goals such as food security (SDG 2), learning opportunities (SDG 4), gender equality (SDG 5), sustainable economic growth (SDG 8), and human health (SDG 3).

Time Series, Modelling, and Predictions

Novo denique perniciosoque exemplo idem Gallus ausus est inire flagitium grave, quod Romae cum ultimo dedecore temptasse aliquando dicitur Gallienus, et adhibitis paucis clam ferro succinctis vesperi per tabernas palabatur et conpita quaeritando Graeco sermone, cuius erat inpendio gnarus, quid de Caesare quisque sentiret. et haec confidenter agebat in urbe ubi pernoctantium luminum claritudo dierum solet imitari fulgorem. postremo agnitus saepe iamque, si prodisset, conspicuum se fore contemplans, non nisi luce palam egrediens ad agenda quae putabat seria cernebatur. et haec quidem medullitus multis gementibus agebantur.

Tsunami and Ocean Hazards

Ocean hazards, such as storm surges, tsunamis or biohazards, can be devastating for the coasts and their communities. They can also have lasting and damaging effects on the coastal landscape, causing long-term coastal erosion, and on marine ecosystems.

Our work on Tsunami and Ocean Hazards

IOC-UNESCO assists and advises policy makers and managers in the reduction of risks from tsunamis, harmful algal blooms, and other coastal hazards by focusing on implementing adaptation measures to strengthen the resilience of vulnerable coastal communities, their infrastructure, and service-providing ecosystems.

With regards to tsunamis, the IOC Tsunami Programme aims at reducing the loss of lives and livelihoods that could be produced worldwide by tsunamis. The IOC-UNESCO Tsunami Unit supports its Member States in assessing tsunami risk, implementing Tsunami Early Warning Systems (EWS) and educating communities at risk about preparedness measures. After sixty years of experience coordinating the Pacific Tsunami Warning and Mitigation System (PTWS), IOC-UNESCO is now leading a global effort to establish tsunami warning systems as part of an overall multi-hazard disaster reduction strategy in order to provide adequate protection at local, national, regional, and global scales.

The IOC-UNESCO Tsunami Programme works closely with the Tsunami Service Providers (TSPs). The TSPs’ main mission is to protect life and property from tsunamis by a constant surveillance of tsunami and earthquake indicators in their Area of Responsibility. TSPs are funded and hosted by IOC-UNESCO Member States on a voluntary basis and subject to evaluation through Key Performance Indicators. They generate and disseminate tsunami forecast information products to regional networks of Tsunami Warning Focal Points (TWFPs). It is the ultimate responsibility of the National Tsunami Warning Centers (NTWCs) of each country, who may also be the TWFP, to evaluate the tsunami information and decide on appropriate national action. In order to ensure citizens are warned as quickly and effectively as possible of the tsunami risks, Member States have developed tsunami response procedures for issuing tsunami warning instructions to their public.

Another key initiative of the IOC Tsunami Programme is Tsunami Ready, which is an international community-based recognition pilot program developed by IOC-UNESCO. It is unfolding in the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea and the Caribbean Sea. The pilot programme enables communities to reach a high level of tsunami resilience by implementing preparedness measures including tsunami drills and exercises, evacuation routes, hazard mapping and signage. Tsunami Ready recognition is not a one-time achievement; it requires ongoing efforts in preparedness measures such as drills and exercises as well as public awareness.

When it comes to ocean biohazards, they fall into several categories, of which the most important is the production of toxins by some species of algae. When these organisms proliferate, they become known as harmful algal blooms (HABs) which can have profound effects on coastal ecosystems seafood safety, and human health. The IOC Harmful Algal Blooms Programme is designed to foster the effective management of, and scientific research on, Hs in order to understand their causes, predict their occurrences, and mitigate their effects. Concepts and national capacity for early warning systems on HABs are developed in close collaboration with Food Agricultural Organization (FAO) and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

World Ocean Day

The United Nations celebrates World Oceans Day every year on 8 June. Many countries have celebrated this special day since 1992, following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held in Rio de Janeiro. In 2008, the United Nations General Assembly decided that, as of 2009, 8 June would be designated by the United Nations as World Oceans Day (resolution 63/111, paragraph 171). Since then, World Oceans Day has been celebrated at UN Headquarters and across the globe. The official designation of World Oceans Day is intended to raise global awareness of the benefits derived from the oceans and the current challenges faced by the international community in connection with the oceans and to emphasize our individual and collective duty to interact with oceans in a sustainable manner so as to meet current needs without compromising those of future generations.

World Tsunami Awareness Day

In December 2015, the UN General Assembly designated 5 November as World Tsunami Awareness Day and tasked the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction to coordinate the commemoration tsunamis disasters worlwide. World Tsunami Awareness Day was established at the suggestion of Japan to call on countries, international bodies and civil society to raise tsunami awareness and share innovative approaches to risk reduction.

IOC-UNESCO is working to reduce the vulnerability of coastal areas to tsunamis in the four ocean basins. The institution, together with its Member States, contribute to World Tsunami Awareness Day through information meetings, round tables, scientific workshops, local exercises, launching of publications, videos and press meetings.

Key figures

- By 2030, an estimated 50% percent of the world population will be under threat of water flooding.

- In the past 100 years, 58 tsunamis have killed more than 260 000 people.

- The hardest one is Indian Ocean’s Tsunami in 2004 which caused an estimate 227 000 fatalities in 14 countries.

Eyewitness of earthquakes and tsunamis

Over the last years, IOC-UNESCO has released a series of movies to to increase the awareness about the Tsunami among over 700 million people live in low-lying coastal areas and Small Islands.

Discover the videos and stories of tsunami’ survivors.

Youth

Today's youth will be tomorrow's leaders and decision-makers. By educating and engaging them on ocean issues, we can help ensure that they have the knowledge and skills to make informed decisions that will help protect and conserve the ocean for future generations.

Youth often bring fresh and innovative ideas to the table. They are not bound by traditional ways of thinking and can bring a new perspective to ocean conservation and sustainability. Their creativity and willingness to experiment can lead to new solutions and approaches to addressing ocean challenges. They can be powerful advocates for the ocean, raising awareness and inspiring others to take action through their energy and enthusiasm.

Youth are moreover on the first line of fire for the long-term impact of environmental decisions on the ocean and the planet. By engaging youth in ocean conservation and sustainability, we can help ensure that they are part of the decision-making and of the co-design of transformative solutions.

UNESCO is working to mobilise youth as agents of ocean action